Optimizations That Aren't, Or Are They?

A few years back, I read a quite unique blog about C++. It was actually one of the first times I was exposed to the concept of technical blogs. And with it the whole concept of learning software development outside the education system (e.g., the good old courses, exercises and sitting in a class being taught by a teacher). It is, to the date, one of my favorite blog posts and a cornerstone in my desire to write my own blog.

The concept of Copy-On-Write

The blog was written by Herb Sutter, more than 20 years ago, and you can find it here. Before discussing the blog and why it is still relevant, more than 20 years later, we need some background. It describes an optimization known as Copy-On-Write, abbreviated as COW. I’m going to cover this optimization both in Rust and C++. Don’t worry, though. I’m going to guide us through the details, and not much background needed in any of the languages. Before we start, a little etymology. In Rust COW actually stands for Clone-On-Write, as this optimization deal with large data. In Rust, we clone, not copy, large data. Yet luckily, both Clone and Copy starts with the same letter, making my life easier to just refer to it as COW. If needed, though, for this post, I’ll interchange the phrases clone and copy all the time. I’m referring to the same thing, the operation of copying a large pile of data from one place to another.

The core idea behind Copy-On-Write is that copying data is a relatively expensive operation. We would preferably do it as little as possible. Let’s understand when it is actually required to copy a piece of data. If you are fluent with the Rust system of ownership (you probably should), your life is straightforward. Any time the ownership system forbid you from doing something, you need to copy the data or find another approach to face the issue (but this is for another day). Anyway, let expand on this for those of you who are less familiar with the Rust ownership system. As long as we have only one variable referring to a piece of data, we have no reason to copy it anywhere. No one can change it under our footsteps, which is the scenario we are afraid of. Copying data is only getting relevant when multiple variables point to the same piece of data. But here comes the optimization part behind COW. Not every time we have numerous variables referring to the same data, we actually have to copy it. If all we do with the data is reading it from various locations, we still have no reason to copy it anywhere. No one is changing it, so we are not exposed to data races. A data race is a situation where we access the data from two different threads, at least one of them mutating the data without proper synchronization. If you are not familiar with data races, I strongly advise researching the topic, as it is vital to almost any developer these days. Anyway, back to COW, the idea is then uncomplicated. Delay the act of copying the data as late as possible. Instead of doing it when we assign a piece of data to multiple variables, to the point we actually write to this piece of data through one of the variables.

Copy-On-Write in C++

Although the core idea is simple, Rust and C++ take different approaches when implementing the optimization. Let’s start with the C++ side, I’ll warn you though it is going to be a gross simplification of things, just to bring you up to the level we need, even if you don’t really know C++. In C++, we will usually have any substantial data as a part of a class, which will have an assignment operator. Any time we assign one variable to another, we will call this assignment operator, which by default, copies the entire data. However, this behavior can be modified, so usually, COW is implemented using this capability. Meaning in C++ COW is not one single abstraction, but rather a unique implementation per class. Traditionally done by modifying the assignment operator to return a new pointer to the same underlying data. Though this is not enough, as now, we might have multiple variables pointing to the same data. So every time we want to mutate the data, we might get into data races, as we discussed before. We could just copy the data on every edit operation, but this would be wasteful. If our variable is the only one pointing to the data, we have copied the information for no reason. Only if we do have multiple references to the data, we need to copy it. Meaning we have to track yet another essential piece of information, how many variables refer to the same data. We increase this shared counter on the assignment operator and decrease it when a variable goes out of scope or on the copying operation. The new copy of the data will get a new counter, with the value of one. Keep in mind this counter for later, it is going to be a key element in this post.

Copy-On-Write in Rust

Unlike C++, Rust really favors safety, strong typing, and explicit abstraction. Therefore, it is unsurprising COW has is own type in Rust, which we put on top of existing data. In Rust COW are enums, which has two states, Owned and Borrowed. For the non-rustacean people, you might want to read my post about Enum & Pattern Matching - Part 1. Owned contains a value of an owned type. While Borrowed has an associated type of reference to a type. This allows the ownership system of Rust to kick in. Meaning each piece of data can have at most one COW variable with the Owned type while having as many Borrowed variables as we want. Through the COW, we can call any method on the underlying class as long as it doesn’t mutate the data. If we do want to mutate the data, we have to call a function on the COW named to_mut. When we call to_mut, a straightforward operation happens. If we are in the Borrowed state, the data will be cloned, while in the Owned state, we just get access to data, meaning it is a no-op. So unlike C++, not all references to the data are born equal. We decide when writing the code, what kind of state our COW will have, which will dictate whether the data will be cloned or not. In Rust COW are a convenient wrapper around a piece of data, allowing us to be agnostic to its ownership, and therefore saving the need to clone the data if we don’t have to. We do have a price to pay when using COW in Rust. The Rust ownership system kicked in once we created a Borrowed COW. Meaning the compiler needs to be able to prove the data will live long enough, forcing us to hold on the original variable as long as the COW is living, something we don’t need to do in C++. All these changes result in a different way of working with the abstraction. Unlike C++, in Rust, it is not completely invisible, we have some work to do. We need to wrap our data in a COW and unwrap it to go back to the original type. Also, we have to call to_mut every time we want to mutate the data.

Is Copy-On-Write a pessimization?

Back to the post, written by Herb Sutter. Although we have seen COWs have a robust and logical foundation, he described in detail how, in many cases, COWs are actually a pessimization. Herb is one of the more influential people in the C++ world, so it is no wonder that eventually, in C++ 11, the practice was forbidden for the string implementation of C++. I assume much thanks to this very post. Later on, I’ll go in detail about why he raises this claim, but first, we should understand in what situation the claims apply. The pre-conditions required, as stated in Herb’s article:

- “The library is built for possible multi-threaded use. This means the degradation can affect you even if your program happens to be single-threaded.”

- “Examples will be in C++, but this discussion applies to any language.”

Those pre-conditions matter as they apply to the Rust use case. Rust’s COW implements the Send and Sync traits, which due to Rust safety requirements, means the implementation is designed to be used in multi-threaded applications. And of course, Herb considers his claims to be valid in any language, not just C++. The bottom line, If Herb is right, we should expect to see degradation in performance every time we use Rust’s COW, even in single-threaded applications. The rest of this post is going to tackle these seemingly contradictory opinions about the effectiveness of COW. I’ll also demonstrate how both parties have valuable evidence to support their claims. And most importantly, we’ll find the middle ground and explains how come everyone is actually kinda right. Finally, I’ll explain why it is Rust who managed to take the upper hand in this specific round of comparison between the languages.

Benchmarking Copy-On-Write in Rust

We can start with the easy front, to prove an optimization is really optimization, all we have to do is to come with a benchmark proving it for some use case. So let’s just benchmark Rust’s COW in a simple use case. It can even be in a single-threaded use case. As we see from the first statement, the fact COW support multi-threaded cases should result in degradation even for the single-threaded case. Our use case will be simple, one of those tasks we get all the time as developers. We have many clients, producing data in a similar, yet different forms, and we have to unify them to the same form for our consumer. Our task will be to get URL, some with the protocol (“https://”) prefix, while others are not, if the URL lack this prefix, we have to add it. Here are 5 different implementations for this task, playing with various ways to receive and retrieve the input and output:

pub fn add_http_prefix_1(input: &str) -> String {

if input.starts_with("https://") {

String::from(input)

} else {

["https://", input].concat()

}

}

pub fn add_http_prefix_2(mut input: String) -> String {

if input.starts_with("https://") {

input

} else {

input.insert_str(0, "https://");

input

}

}

pub fn add_http_prefix_3<T: AsRef<str>>(input: T) -> String {

if input.as_ref().starts_with("https://") {

String::from(input.as_ref())

} else {

["https://", input.as_ref()].concat()

}

}

pub fn add_http_prefix_4(input: &str) -> Cow<str> {

if input.starts_with("https://") {

Cow::Borrowed(input)

} else {

Cow::Owned(["https://", input].concat())

}

}

pub fn add_http_prefix_5(input: Cow<str>) -> Cow<str> {

if input.as_ref().starts_with("https://") {

input

} else {

match input {

Cow::Owned(mut input) => {

input.insert_str(0, "https://");

Cow::Owned(input)

}

Cow::Borrowed(input) => {

Cow::Owned(["https://", input.as_ref()].concat())

}

}

}

}

The first three methods are the usual suspects, each doing the same task, the first only borrow the input, the second take full ownership, and the third is templated, allowing the user to chose whether to lend or give us the value. In all cases, we have to return a new owned string, as we might edit the input. The fourth implementation borrows the data, but instead of always creating a new string, it takes advantage of the fact that in some cases, we don’t actually need to edit the input. It allows us to retrieve the borrowed variant of COW when nothing changes, and the owned version when we do edit the input. The fifth implementation takes it one step further and tries to get the input as a COW as well.

It is my first time benchmarking code in Rust, I chose to use criterion as it seems to be the goto crate for these kinds of tasks. The benchmarks were performed on my home PC, Intel i7 8700 machine, with 16 GB of RAM running Windows 10. I tried to shutdown as much of the background noise as I could during the benchmarks. And here is my very basic benchmarking code:

pub fn criterion_benchmark(c: &mut Criterion) {

c.bench_function("test1", |b| b.iter(|| cow_perf::add_http_prefix_1(black_box("test"))));

c.bench_function("test2", |b| b.iter(|| cow_perf::add_http_prefix_2(black_box(String::from("test")))));

c.bench_function("test3", |b| b.iter(|| cow_perf::add_http_prefix_3(black_box("test"))));

c.bench_function("test4", |b| b.iter(|| cow_perf::add_http_prefix_4(black_box("test"))));

c.bench_function("test5", |b| b.iter(|| cow_perf::add_http_prefix_5(black_box(Cow::Borrowed("test")))));

c.bench_function("test1_2", |b| b.iter(|| cow_perf::add_http_prefix_1(black_box("https://test"))));

c.bench_function("test2_2", |b| b.iter(|| cow_perf::add_http_prefix_2(black_box(String::from("https://test")))));

c.bench_function("test3_2", |b| b.iter(|| cow_perf::add_http_prefix_3(black_box("https://test"))));

c.bench_function("test4_2", |b| b.iter(|| cow_perf::add_http_prefix_4(black_box("https://test"))));

c.bench_function("test5_2", |b| b.iter(|| cow_perf::add_http_prefix_5(black_box(Cow::Borrowed("https://test")))));

}

fn custom_criterion() -> Criterion {

Criterion::default()

.sample_size(1000)

}

criterion_group!(

name = benches;

config = custom_criterion();

targets = criterion_benchmark);

criterion_main!(benches);

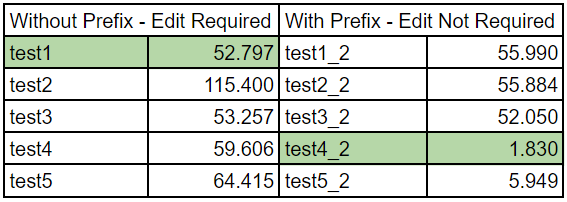

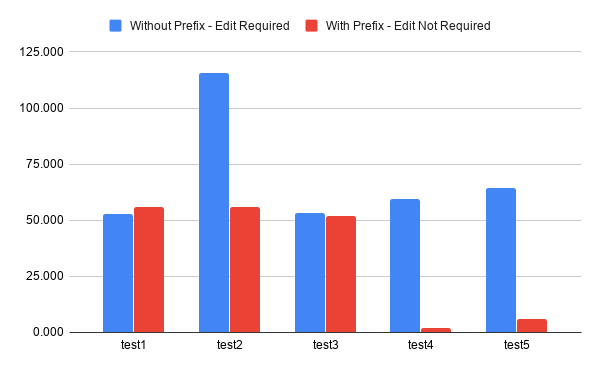

And without furhter a due, a simplified view of the benchmarking results:

Digging deeply into the result is behind the scope of this post. Some of you might even notice I didn’t provide the raw data. I do, however, give you all the information needed to reproduce the results. Also, before diving into the numbers, note benchmarking is a complex topic, more than people usually give credit to. The results shown here are not necessarily the most accurate or illustrate the exact benefit/loss for each of the implementation. They should be good enough to understand the trend, especially when they match what we actually expect to see. We will narrow down the results only to the part we care about, seeing if COW actually improves the performance. I’ll focus only on the first and fourth implementations. The first implementation, while not having the best average among the non-COW implementations, has the best performance when mutating the data is required. The fourth implementation is the best one among those utilizing the COW optimization. The results are quite easy to analyze. When we need to mutate the data, COW is slower. At this specific test, the fourth implementation is slower by 13% in comparison to the first implementation (but it might not always be the case). On the other hand, when we don’t have to mutate the data, the fourth implementation managed to outperform by 96% the first one.

The bottom line, when using COW in Rust, we pay a small price every time we need to mutate the data but gain a huge benefit when all we want is to do is to read the data. There are a lot of use cases where this behavior can be utilized to improve performance. This is definitely doesn’t looks like the pessimization Herb discussed mentioned.

Understanding why Copy-On-Write might be a pessimization

Checking Herb’s claims is much harder. We can come up with a benchmark where the application of COW in C++ actually reduces performance. Herb even shared some of those in his post. But this is not enough, as someone can rightfully claim the problem was in a specific implementation, or provide us with a use case and a benchmark where it does help. Herb’s claims are more profound, they reach to the core of this very optimization. He states that something in the heart of this optimization leads to reduce performance in a multi-threaded world. So we have no way around it, but to actually understand his claims.

At the core of Herb’s claim, is the fact that there are operations which are even more expensive than copying data, in our case, we are talking about data synchronization. When we have to synchronize data, which is accessed concurrently, it will usually require more time than just copying the data. Now, if we want to keep COW invisible to the user as we do in C++, all references to the data shared by a COW must act the same, whether there is only one such variable or not. Unlike Rust, we can’t require that one should live longer, or tag those references in any way, as we don’t do it for references not using the COW optimization. As we’ve seen before, it will leave us in a situation where without any additional data, we won’t know if to copy the shared data or not. Earlier, we’ve used a reference counter to make this decision. And it is precisely this shared counter which needs to be synchronized, as it is being accessed concurrently. Each of these accesses can potentially alter the value of the counter. Herb’s claims and demonstrates that this synchronization cost is higher than the performance boost gained by saving the copying of the data.

Rust’s smart design choice

Now we’ve seen that in Rust’s case, we can avoid the cost of synchronization with a smart design. But we’ve also paid the price, COW are not invisible in Rust, we have to be explicit about using them. Let’s understand how Rust avoids the extra synchronization cost. Unlike the standard module of COW, implemented all around in C++, Rust takes a different approach. As we’ve seen, COW in Rust only enables us to be agnostic to the ownership of the data. The essential and subtle issue to understand here is that we know the ownership in compile time. True enough, it is being determined by the input at runtime, but for any given value, the result is deterministic, we will either own the data or borrow it. In our example, in case the data had a prefix of “https://” we only borrowed the data. Otherwise, we had ownership of the data. We decide whether to copy the data exclusively according to the ownership information, which, as we saw, we know at compile time. As a result, we don’t need to keep extra information shared between the different references to the data. Hence Rust COW doesn’t suffer from the extra costs required to synchronize additional information and does provide a real optimization, even in a multi-threaded environment.

So we’ve seen how a small change in the way we build the COW abstraction allowed us to keep its benefit even in a multi-threaded environment. The price we had to pay might be neglectable in many scenarios, but it does exist. It can still render the benefit of COW obsolete, as we might have to keep the original piece of data for a more extended period than actually required. Also, editing the data is more expensive as well.

Why C++ lost to Rust in this front

Now we are left with one final issue. So Rust designers managed to come up with an excellent design that overcomes the weakness Herb found in COWs. It seems relatively a small price to pay when we do need the extra juice in our program. But does this design is unique to Rust, or was it an oversight on Herb’s behalf, meaning C++ is capable of this abstraction? The answer is a little more complicated than I would like. In practice, nothing is impossible in C++, and yes, we can try and create a class similar to COW in C++. But C++ lacks a critical feature to actually make it viable, Rust’s lifetimes. We have no way to convey the requirements to keep the original data in C++. Sure enough, we can guide our users that they need to keep the original variable around long enough. It is not like C++ never heard of unsafe things before. Though when COW is nested as a member inside another class, users of that class are not even aware COWs are being used. It would be almost impossible to keep track that the required data live long enough. Even in C++ standards, this unsafety is unacceptable. Which got us to a point where Rust safety actually helps us gain performance over C++, as some abstractions are just too unsafe. Yes, even for C++.

The bottom line is that Herb was kinda right in pointing out the deficiencies in COWs. To keep the optimization viable, Rust made some sacrifices in the optimization capabilities and ease of use. COWs in Rust are more involved, and they have more requirements in order to work (keep the original data living long enough). Also, not everything possible in C++ COWs is possible in Rust. Most notably, adding COW after the fact inside a library is impossible, as the user must be aware of it. Yet Rust designers were also right, COWs in Rust do provide a good possibility for optimization if used properly. I find it as a pleasant middle-ground between what seemed like an opportunity for endless debates between C++ and Rust advocates. But while we did find a decent middle-ground and managed to settle between the different claims, one language made out of this topic as a clear winner. Rust design for safety, and the very well designed lifetime feature, allowed Rust to create a better abstraction than we could ever dream on in C++. And in this specific case, we also saw how such a notion can actually lead to improved performance. A very sweeping win for Rust.

Read more: